Research ProjectInvasive Species Rafting on Ocean Plastics

Affiliated Labs

Project Goal

To evaluate the role of floating plastic pollution in transporting species across oceans to non-native ranges.

Description

Plastic pollution in the oceans is known to endanger marine wildlife and degrade habitats. Floating plastics can also transport marine animals, plants, and microbes long distances across the oceans through ‘ocean rafting’. While floating in nearshore environments, local marine species, such as mussels, amphipods, and barnacles, can settle on plastic litter. Because plastics are exceptionally buoyant and slow to degrade, floating plastics in coastal waters can be carried out to sea by offshore ocean currents, where the debris and the attached organisms can circulate for years, in some cases, traveling far enough to reach new shores. Marine organisms hitchhiking on plastics can thus be deposited hundreds of miles from their native ranges, increasing opportunities for non-native species introductions.

An extreme example of plastics’ efficacy in transporting coastal organisms across oceans followed the 2011 Japan tsunami when 5 million tons of debris washed offshore. One year later, some of these derelict objects (for example, vessels, docks, buoys, household items) began floating ashore on the west coast of North America and Hawaii. Researchers from SERC and other institutions as well as over 100 volunteers tracked the arriving tsunami debris for the next six years, collecting over 600 items. They found 289 Japanese marine species living on the debris, thirty of which were known invasive species. Their discoveries, published in Science, were unprecedented given the length of time that the coastal hitchhikers floated at sea (over 5 years in some cases) and the extraordinary distance traveled before landing on North American shores.

Following the Japanese tsunami debris effort, SERC researchers continue to investigate how ocean plastics contribute to species dispersal and future biological invasions. Current projects include:

- Risk Assessment: Quantifying the risk of invasion along the west coast by the tsunami debris hitchhiker

- Open Ocean Hitchhikers: Determining the prevalence and condition of coastal marine species found attached to floating plastics in the open ocean

- Offshore Mooring Monitoring: Investigating the development of marine communities on floating plastics at different distances to shore, using offshore moorings

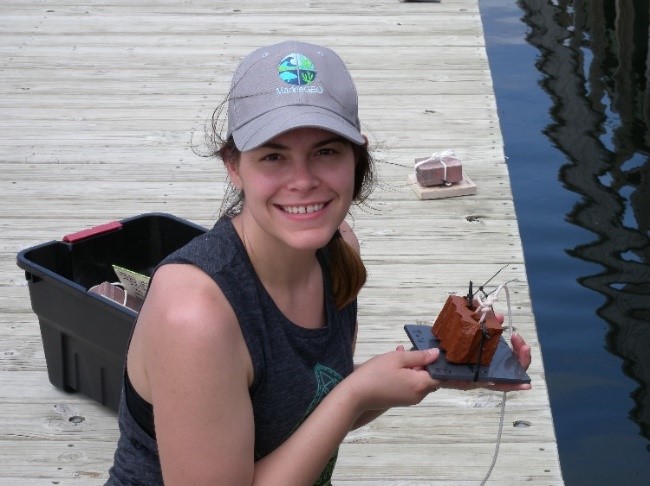

- Settlement on Plastic Debris: Evaluating the effect of plastic type on settlement of coastal marine species, especially known invasive species

Contact

Postdoctoral fellow Linsey Haram, HaramL@si.edu

Miller, J. A., R. Gillman, J. T. Carlton, C. C. Murray, J. C. Nelson, M. Otani, and G. M. Ruiz. 2018. Trait-based characterization of species transported on Japanese tsunami marine debris: Effect of prior invasion history on trait distribution. Marine Pollution Bulletin 132:90–101.

Therriault, T. W., J. C. Nelson, J. T. Carlton, L. Liggan, M. Otani, H. Kawai, D. Scriven, G. M. Ruiz, and C. C. Murray. 2018. The invasion risk of species associated with Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris in Pacific North America and Hawaii. Marine Pollution Bulletin 132:82–89.

Carlton, J. T., J. W. Chapman, J. B. Geller, J. A. Miller, D. A. Carlton, M. I. McCuller, N. C. Treneman, B. P. Steves, and G. M. Ruiz. 2017. Tsunami-driven rafting: Transoceanic species dispersal and implications for marine biogeography. Science 357:1402–1406.

Miller, J. A., J. T. Carlton, J. W. Chapman, J. B. Geller, and G. M. Ruiz. 2017. Transoceanic dispersal of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis on Japanese tsunami marine debris: An approach for evaluating rafting of a coastal species at sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 132:60–69.

National Geographic. “Invasive species are riding on plastics across the oceans” by Whitney Pipkin. Aug. 28, 2018.

Live Science. “Marine invaders: Japanese tsunami brought 300 species to US shores” by Megan Gannon. Oct. 2, 2017.

BBC News. “Tsunami drives species ‘army’ across Pacific to US Coast” by Matt McGrath. Sept. 29, 2017.

Nature. “Tsunami wreckage serves as liferafts for invasive species” by Rachael Lallensack. Sept. 29, 2017.

NPR All Things Considered. “Animals, plants rafted across the Pacific after Japan's 2011 earthquake” by Ailsa Chang. Sept. 29, 2017.

Smithsonian Magazine. “The 2011 tsunami flushed hundreds of Japanese species across the ocean” by Jason Daley. Sept. 29, 2017.

The New York Times. “After the tsunami, Japan’s sea creatures crossed an ocean” by Martin Fackler. Sept. 28, 2017.

Popular Science. “Tons of living animals have floated from Japan to Oregon on plastic junk” by Ellen Airhart. Sept. 28, 2017.

Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. “Tsunami enabled hundreds of species to raft across Pacific” by Kristen Minogue. Sept. 28, 2017.

The Washington Post. “Plastic junk brought invasive species to U.S. after Japan’s 2011 tsunami” by Ben Guarino. Sept. 28, 2017.

Hakai Magazine. “Strangers on the shore” by Larry Pynn. Oct. 21, 2015.

EARTH Magazine. “Setting sail on unknown seas: the past, present and future of species rafting” by Mary Caperton Morton. February 24, 2013.