Originally Published on January 20, 2017 on the Shorelines Blog

(Kim Holzer)

The U.S. is on the brink of a natural gas boom—but that could expose its shores to more invasive species, Smithsonian marine biologists report in a new study published this winter.

Over the last decade, U.S. natural gas imports have dropped as the country tapped into its own resources. Now, thanks to new technology that makes it easier to extract and store natural gas, it’s poised to be the world’s third largest exporter of liquefied natural gas by 2020.

“We’ve hit an inflection point,” said Kim Holzer, lead author and biologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). Exports haven’t yet reached historical import highs, but they are climbing.

Within the U.S., natural gas moves mainly via pipelines. When shipping it abroad, it’s much more efficient to carry it in liquid form. But to turn natural gas into a liquid, it needs to be cooled to -162 degrees Celsius, or about -260 degrees Fahrenheit. Until recently, the only U.S. facility that exported liquefied natural gas was in Alaska. However, in February 2016, the first tanker with liquefied natural gas from the lower 48 states set sail from Louisiana to Brazil. Since then, several more terminals that can export liquefied natural gas have cropped up, including one on the Chesapeake in Maryland’s Cove Point.

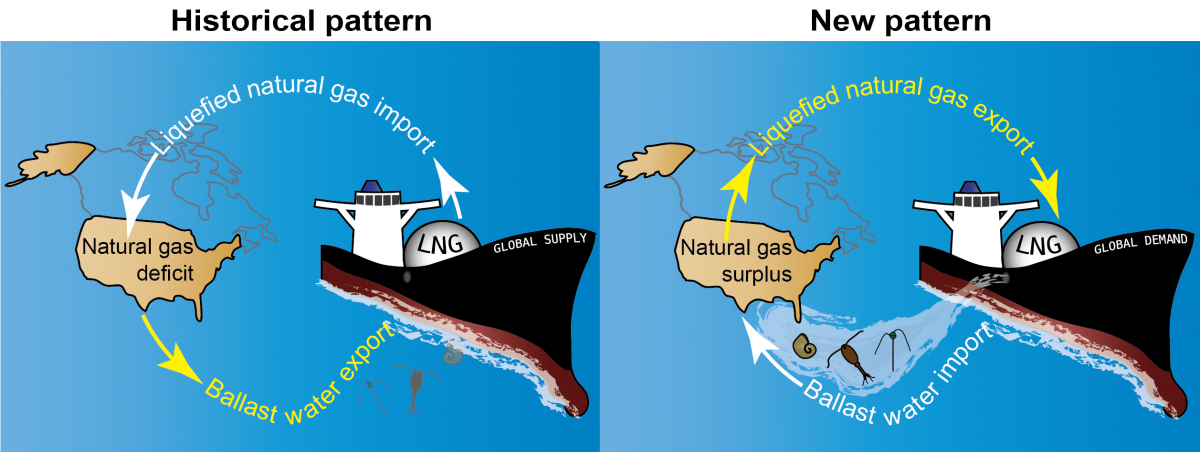

The invasive species threat comes from ballast water: water large ships carry in tanks for balance, which can be teeming with non-native creatures. When vessels bring liquefied natural gas into the U.S., they carry minimal ballast water. But when vessels with that cargo leave the U.S., they come back loaded with ballast water that they typically discharge in U.S. harbors. A single liquefied natural gas tanker can carry enough ballast water to fill 23 Olympic-size swimming pools.

“When people think about consequences of energy development, they typically focus on infrastructure, like pipelines, and the commodity itself, not the transport process and what may hitchhike inside the ships,” Holzer said.

Holzer and other biologists from SERC’s Marine Invasions Lab reported their discoveries in the journal Science of the Total Environment. The team calculated how much ballast water liquefied natural gas tankers bring into the U.S. now, and how much that number could grow by 2040 based on projected market demand. Their best estimate saw a 90-fold increase in ballast water from liquefied natural gas exports compared to 2015. That was on the more conservative side—if oil prices go up, the ballast water influx from liquefied natural gas could shoot up even more.

The U.S. Gulf Coast would face the biggest flood of that new ballast water, as it houses the most approved or proposed facilities for handling liquefied natural gas exports. But harbors with similar facilities along the Atlantic, like the site in Cove Point, Md., would also be on the front lines.

There are ways to make ballast water less dangerous. Today, commercial ships are required to do “open ocean exchange” – flushing their coastal ballast water out in the open ocean. The hope is that when they discharge the new water in U.S. ports, those open-ocean species won’t do as well. Of course, that only works for vessels that pass through the open ocean, or 200 nautical miles offshore. Some harbors also have facilities that can accept ballast water on land and give it the same treatment as municipal water. But a more comprehensive option, which would work even for ships that don’t enter the open ocean, is treating ballast water onboard using chemicals or ultraviolet radiation. That technology is only just getting off the ground. As of December 2016, three on-board treatment systems had earned the U.S. Coast Guard’s stamp of approval, but it could be years before they become standard on cargo ships.

The threat to the U.S. is real. But, Holzer points out, trade goes in two directions, and it’s equally important to remember that the U.S. exports potential invaders of its own.

“What happens when we import goods and send our ballast water to other places?” Holzer asks. “There’s a shared interest and an international responsibility to understand how that affects the World Ocean and global dispersal of species.”

It’s just one more reason making ships able to rid their ballast water of potential invasive species on board is so critical. For inventors and ship managers, it’s a race against time.

Citation:

Holzer, Kimberly K.; Muirhead, Jim R.; Minton, Mark S.; Carney, Katharine J.; Miller, Whitman A.; Ruiz, Gregory M. (2017) Potential effects of LNG trade shift on transfer of ballast water and biota by ships. Science of the Total Environment. (early access online) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.12.125