Aug 1, 2011

This summer’s interns are learning what ecological research is all about: repetition, experimentation and trial-and error, hard work, and occasionally a new discovery.

Every year the arrival of summer interns provides much needed assistance during the busy field season when most ecological research happens. The Marine Invasions Lab hires several college students or recent college graduates under the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center's (SERC) Internship Program. During the summer the interns participate in several different research projects as well as conduct their own independent research. This year’s interns have participated in several projects including the nearshore surveys in the Rhode River, ocean acidification research, removal of the European Green Crabs and Didemnum vexillum (D. vex) in California.

One of the more exciting events of the summer was the discovery of a Northern Snakehead fish (Channa argus) in the Rhode River in Edgewater, Maryland. Interns Diana Sisson (Warren Wilson College) and Philip Choy (University of California Davis), along with visiting student Alison Everett and SERC Scientists Eric Bah and Stacey Havard, caught the nonnative fish in a seine net during the monthly nearshore survey. The Northern Snakehead is native to Asia and is a major concern in Chesapeake Bay because it is a voracious predator that can impact native fish species. The discovery of the snakehead provided the opportunity to think about science in a new way and helped put together the information they’d learned. Discoveries like this one demonstrate the importance of long-term surveys and often inspire scientists to pursue new lines of research. For Diana, “the taste of discovery was more addictive than chocolate”. And each of them had the opportunity to participate in the media story that their

discovery generated, providing yet another educational opportunity.

But for many of us, the summer field season doesn't result in the kind of discoveries that end up on the evening news; rather the field season brings a series of experiments sorted out through some on-the-fly trial and error. For interns Jennifer Fasciano (SUNY College at Brockport) and Kiersten Newtoff (Radford University) this came as a surprise. Prior to their experience here, they hadn’t considered that new experiments aren’t conducted from an established protocol; rather the protocol is created through trial and error in the early stages of the experiment. Environmental research plans and proposals, while well thought out, rarely go as planned and researchers must adapt to various sets of circumstances. Jennifer and Kiersten spent their summer measuring the pH and carbonate chemistry in and around the Rhode River. Their plan was to put containers of young oysters at several sites in the area and conduct experiments to test oyster growth at differing levels of carbon dioxide (CO2). Unfortunately the oysters didn’t survive in all the locations originally proposed, so they spent a lot of time and effort looking for a suitable place to conduct the experiment. This unexpected hurdle delayed the experiment and prevented them from conducting the large independent project they had planned; however, that didn’t stop them from learning a lot about estuaries, oysters, and ocean acidification.

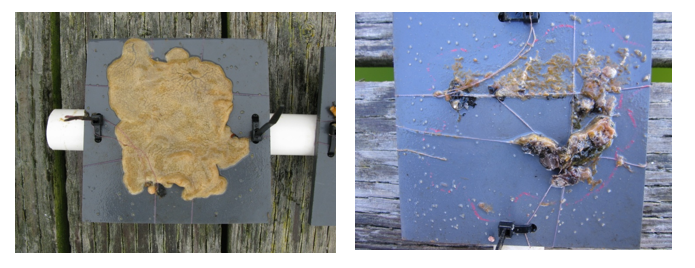

Interns Benson Chow (San Francisco State University), Michelle Repetto (University of South Carolina) and Erin Swift (Simons College), working in our laboratory at the Romberg Tiburon Center in California, had a similar experience. As they worked to set up an experiment looking at the introduced tunicate D. vex, they were amazed at how well researcher Linda McCann was able to quickly come up with an alternate sampling method when the intended method failed. Benson and Linda now have a smoothly running experiment in which PVC plates containing established colonies of D. vex (image) are placed in several different treatments, including acetic acid (vinegar), bleach, low dissolved oxygen, and more, to see if they survive. This experiment, like the one in Maryland, illustrates the need to modify and adapt to changing circumstances and was an eye opening experience for all three interns. It is also great training for graduate school, which they all intend to pursue.

While the interns working on projects at SERC’s main campus in Maryland had the advantage of working closely with several research professionals, Michele and Erin in California had the opportunity to work somewhat independently. For much of the summer Michele and Erin studied and worked to control an introduced population of the European Green Crab (Carcinus maenas) in Seadrift Lagoon (Stinson Beach, CA), contributing to a three year project that attempts to control the population through trapping and removal. Every other week they set out traps baited with sardines to catch the green crabs. At the start of the summer they were catching as many as 1200 crabs per week. With a catch this large they needed to organize and manage a team of local volunteers to help with the effort. But over time the number of crabs caught decreased, freeing them up to conduct their own experiments in the lagoon. Michele wanted to understand what the crabs were feeding on and collected sediment core samples to find out. Erin wanted to know why they were only catching large crabs and set out to find larval crabs (zoea) in the plankton. At the end of the summer they will each present the results of their independent projects to our SERC scientists based at the Romberg Tiburon Center.

The goal of the intern program is not simply to gain extra help for our field experiments, it is to provide training and mentoring to students in ecology and help prepare them for careers in this field. All of the students interviewed for this story felt that the experience they gained at SERC prepared them for graduate school, inspired them, and challenged some of their preconceived ideas. Without exception, their favorite part of the summer was the field work – getting outside, seeing and learning about marine invertebrates and chemistry, and even getting dirty and having minnows nibble at their knees.